A painter of unquestionable originality and equally great constancy of creativity, Alexandra Exter is the artist to whom we owe the birth of constructivist painting in Russia. After a Cubist period in Paris between 1910 and 1912, Exter rapidly moved on to incorporate the principles of the Futurist dynamic into her work. Inspired by Malewicz’s revolutionary Suprematist work, with which she had been actively involved in the Fall of 1915, and this before all her “non-objectivist” comrades (the term was used in Moscow for the first time in relation to paintings by Exter exhibited in 1915), she nonetheless went on in 1916-1918 to develop a language of abstract forms and a logic of compositional structures free of allegiance to the unconditionally autonomous aesthetic of Suprematism.

Attracted during her first period in Paris (1910-1914) to the prospect of a new decorative art based on Cubo-Futurist principles, she was at the origin of the first exhibitions of modern decorative art (Moscow 1915 and 1917). Thereafter she was to develop her extraordinary talent in the field of stage design.

After having lived through the disasters of the civil war, in both human and material terms, Exter sought to leave South Russia as early as 1919. Finally in June 1924, on the pretext of mounting her works at the Venice Biennale, she escaped the Soviet Union. After a brief stay in Italy, she arrived in Paris at the end of the year and lived there until her death in 1949.

Throughout the nineteen twenties and thirties, Exter divided her time between painting works of the “purist” type, designing stage decors, teaching, and book illustration where her talent flourished phenomenally but which has yet to attract the attention it deserves. The same is true of for her abstract painting, the originality of which has still not been thoroughly perceived. Her “constructive” originality and the variety of her pictorial inventions are such that art critics accustomed to classifying works based on clichés of “geometric styles” remain disoriented. Thus, at a recent “constructivist” exhibition at the Tate Gallery in London, Exter’s work was included “hors catalogue” alongside Rodchenko’s and Popova’s, artists that for decades have set the tone of formalist classifications, if not already “post-modernists”.

In the last decades of the 20th century, a period marked by the rediscovery of Russian constructivism, her close ties to Western art and her status as a refugee stood in the way of the recognition her work should have received in her native Russia. All the more so since her painting was often at the forefront the avant-garde and Russian art scenes in the 1910s. Because of her friendships with both Malewicz and Tatlin, she often played the role of peacemaker during the typically avant-garde conflicts that erupted ineluctably. This was the case during preparation for the 0,10 exhibition (December 1915), which could have ended in disaster without Exter’s diplomatic mediation. The loss of many of her paintings, left in 1917 in the home of her former father-in-law where she had a studio, was another obstacle to the recognition of the significance of her pure pictorial work.

Highly appreciated in both personal and artistic terms, “Madame Exter”, as she was respectfully known in Moscow and Saint Petersburg, had a key role in the modernist constellation in Russia, participating in most of the exhibitions that marked the rise of non-objective painting. In Kiev, her role was indisputably preponderant. After her return to Paris in 1925, she had a no-less first-rate European career. Although, due to the general loss in interest in abstract art in Europe at the time, the focus of Exter’s creative work concentrated on stage design. She did, however, suffer from a lessening of opportunities for modernist artists starting in the thirties. This, added to health problems, made her life increasingly difficult. Deprived of professional opportunities, by the end of the twenties, she was forced to retreat to a modest house in the Parisian suburb of Fontenay-aux-Roses.

Shortly before she died, Exter bequeathed her studio and documentation to a Russian friend, a painter who had immigrated from Kiev to Paris and subsequently to the United States. A revival of interest in her work began only in the early seventies, but much remains still to be done before her work can gain its rightful place in 20th-century art.

* * *

Born in Bialystok (today a Polish city) Alexandra Exter (née Grigorievitch) lived out her childhood and adolescence in Kiev. Kiev was a city of cosmopolitan culture, very receptive to contacts with the West, which it maintained as much with Cracow and Dresden as with Munich, Vienna, and Paris. Far from the overweening ambitions that poisoned relations in Saint Petersburg and from Moscow’s intense competitiveness with regard to Saint Petersburg and Paris, a certain relaxed provincial atmosphere freed young artists in Kiev from pretentions to superiority. News of new artistic developments in the West arrived as quickly in Kiev as in Moscow, but stirred less competitive reactions. Its cosmopolitan population (Moldavian, Jewish, and especially Polish), with their European aspirations, absorbed these influences in a non-partisan way. Exter developed also a facility in early childhood for other languages and cultures. After finishing her studies in the local Fine Arts school, the young Exter, whose charm and talent facilitated her social ascension, had but one desire: to pursue her studies in Paris, indisputable capital of world art at the time.

When she went to France for a few months in 1907, she spent time in the “academies” (free studios) of Montparnasse, in particular in the studio of Carlo Delvall at the Grande Chaumière. In 1910, she rented a studio on a permanent basis at 10 Rue Boissonade right in the heart of Montparnasse. Here too her charming personality and intelligence full of finesse quickly opened doors for her. She was a frequent visitor to the Parisian salon of Elisabeth Epstein, a Russian student of Matisse and friend of Kandinsky and Delaunay, and to the salon of Serge Férat, patron of the journal Les Soirées de Paris, headed by Apollinaire in 1912-1914. Her relationship to Robert and Sonia Delaunay opened other artistic and social prospects for her; through them she met the Cubist collector and art historian Wilhelm Uhde and the Berlin gallery owner Herwerth Walden, a fervent champion of the Delaunays and of the most daring new European painting. Through these relations, she also met the Futurist art critic and painter Ardengo Soffici, with whom she had a love relationship during the “Soirées de Paris” years. Soffici left some highly romanticized, not to say frivolous, descriptions of their liaison in his memoirs, a romantic elaboration which artistic importance has been lately highly exaggerated by some superficial art critics.

Drawn as much to Cubism as to Futurism, Exter was soon caught up in a social and artistic whirlwind in Paris that was hardly restricted to Cubist orthodoxy alone. For her avant-garde friends – in particular the poet Benedict Livshitz, and the painter and editor David Burljuk – her trips back to Kiev were transformed into festivals of modernity, as she came with new publications, photos, and even original works. She also organised important avant-garde events like the Kol’tso exhibition (The Ring, 1914), the only real Futurist exhibition in Kiev if not in the whole of southern Russia. Compared to the entrenchment of Moscow and the provincialism of Odessa, Kiev had the atmosphere of a true European capital.

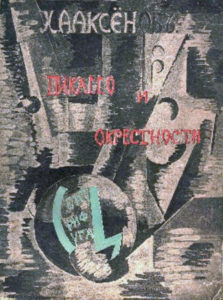

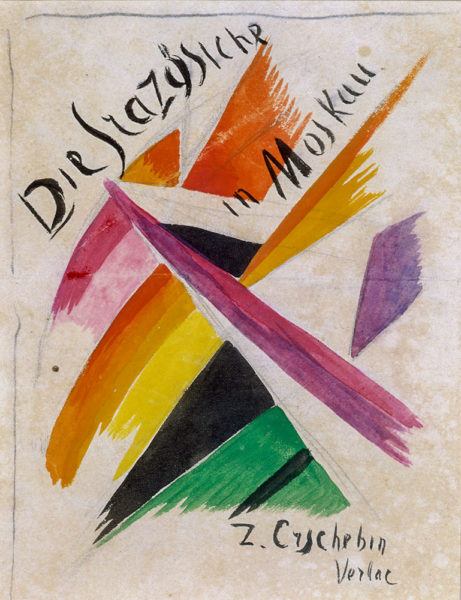

Picasso et les alentours

In Paris, Exter participated fully in modernist activities. We find her at the Salons des Indépendants and at the Section d’Or exhibition (Fall 1912), a pivotal event that liberated Cubo-Futurism from the narrowly “geometric” framework into which anti-modernist critics has hastily categorized nascent Cubism. She spent time at Brancusi’s studio and at Archipenko’s, and helped the young art critic Ivan Aksionov write his remarkable essay on Cubism Picasso i okrestnosti (Picasso and its environment). Written in 1914, published in Moscow in 1917 with a cover illustration by Exter, and largely forgotten for many a long decade, the essay was not only one of the first critical texts on Cubism in its day, it was also the first publication with Picasso’s name in the title.

Even when she was living and working in Paris, already Alexandra Exter continued to join in the activities of the Russian avant-garde. As a member of the Saint Petersburg Youth Union and of the Moscovite Jack of Diamonds group, she took part in the annual exhibitions of both organisations starting in 1910. She was so well connected in Parisian circles that Davis Burljuk asked her already in 1910 to act as an intermediary to Fauconnier in view of organising a “Russian section” at the Salon des Indépendants. And her artwork was so well regarded in Parisian modernist circles that Herwarth Walden proposed her at the end of the spring of 1914 to organise an exhibition in his Berlin gallery Der Sturm. The outbreak of the war thwarted his plans, but that spring Exter was features along with several Russian comrades at the International Exhibition of Futurist Painters and Sculptors at the Sprovieri Gallery in Rome.

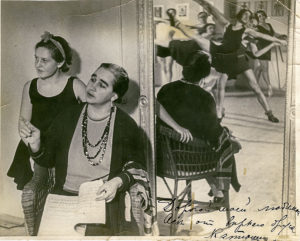

The war brutally interrupted what looked like a promising career in the West. For the next ten years, Exter found herself stuck in Russia. Back in Kiev, she opened her studio in 1917 to students and soon discovered that she had a real talent for teaching. For two years, her studio became the centre of avant-garde art in the city, where writers, poets, musicians and dancers would come, and conferences were held. Lissitzky, Rabinovitch, Ilia Ehrenburg, whose wife Vera Kozintzeva was a student of Exter, his brother the future filmmaker Grigori Kozintzev, the Polish composer Karol Szymanowski counted among those who spent time at her studio. The dancer Bronislawa Nijinskaja offered Exter the possibility of working on show that she was putting on in Kiev and elsewhere.

Fleeing the very brutal civil war in Kiev, Exter moved to Odessa for several months in 1919, hoping to find a way out of the country as many of her friends did, unfortunately in vain.

Soon after the death of her husband in 1917, her mother passed away in Odessa. The fight that ensued over the heritage, at the instigation of her father-in-law, dispossessed her of a good part of the paintings she had left in a house in Kiev. Many of these were destroyed in the violence of the civil war.

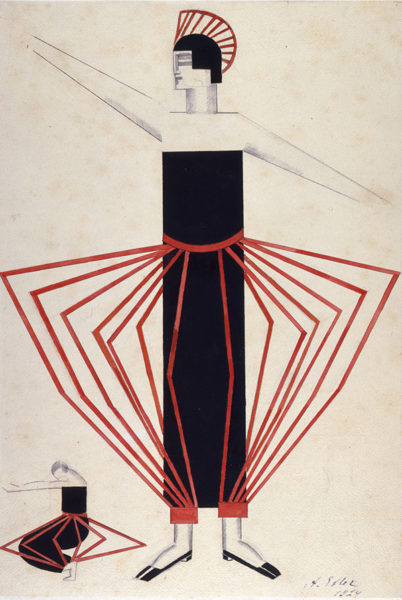

An invitation from Moscovite director Alexandre Tairoff, with whom Exter had already worked in 1916 and 1917, finally gave her the opportunity to escape the disastrous effects of the civil war, which were particularly brutal in the South. Back in Moscow at the end of 1920, Exter immediately joined the new art groups and social organisations, dominated at the time by the constructivist wing of the avant-garde. Her own output went through a new flourishing period of development. Exter was actively engaged in some of the boldest avant-garde enterprises of the time, such as the constructivist exhibition 5×5=25 (September 1921) that marked the apogee of the most radical non-objective painting. Abstract forms reached a conceptual turning point that the young art historian Nikolai Tarabukin no sooner qualified as the “end of pictorial practice” and the “suicide of painting” (see his book From Easel to Machine, Moscow 1923). Aside from her activities in the field of stage design, Exter taught in Moscow in the “Free workshops” (Vkhutemas), worked for Lamanova’s fashion studios and for the movies, making costumes for the science-fiction film Aelita. Directed by Yakov Protozanov in 1923 and released at the beginning of 1924, Aelita remains one of the most visually daring and innovative films of its day. In 1923, she also conceived or created some of the decor for the first Pan-Russian Exhibition of Agriculture and Industry and designed uniforms for the new Red Army.

Exter was already celebrated for her stage designs for Famira Kifared (1916) and Salome after Oscar Wilde (fall 1917) directed by Tairoff at the Kamerny Theatre. Salome was so well received in artistic circles in Moscow, that it was seen as more important than such political events as the coming to power of the Bolshevik faction, the historical consequences of which were not easy to evaluate in October 1917. Familiar as she was with the new stage design ideas featured in the Diaghilev ballets in Paris between 1910 and 1913 (the work of Bakst as well as the revolutionary contribution of Vaclav Nijinsky in Afternoon of a Faune), Exter brought a wind of undeniable novelty to Moscow, extending the innovative surge with her own radical inventions.

Her great innovation was to dematerialise the decor by replacing fixed panel sets with a pure light construction whose spatial logic was as rigorous as it was dynamic. In October 1917, the bright austere structure of Salome marked the birth of theatrical Constructivism. The staging was a triumph. By dematerialising the decor, Exter prolonged in a non-objective (abstract) manner the dramatic austerity of Gordon Craig’s monumental décor which has been well known and appreciated in Russia.

In his comments on this new staging, Alexandre Tairoff underscored the revolutionary contribution of Exter’s stage set, which was built up in vertical planes instead of being designed in a frontal (perpectivist) way. In his Notes of a Director he wrote in 1921: “Exter drew on her Cubist experience”. This principle of vertical construction culminated in the spectacular and baroque staging of Romeo and Juliet in 1920.

The fall of 1917 saw the triumph of Exter’s painting in Moscow at the annual Jack of Diamonds exhibition, whose president at the time (if for a very short moment) was Kazimir Malewicz. With two entire rooms featuring ninety-two works, including mostly theatre costume projects and a few abstract and Cubo-Futurist paintings, the artist’s participation can almost qualify as her first individual show – a view that was explicitly expressed by some of the critics at the time. Whereas the critics Tugendhold and Efros focused in particular on the coloristic radiance of Exter’s artworks, the public appreciated the “narrative” vivacity of her work more readily than the monastic austerity of Malewicz’s Suprematism.

Exter continued to be active in modernist events in Moscow and Saint Petersburg throughout the 1910s. In the spring of 1915, she participated in the very radical avant-garde exhibition Tramway V held in Saint Petersburg right in the middle of the war, with works selected by Malewicz. Exter showed 14 major Cubo-Futurist paintings. These included several “urban landscapes”, Futurist views of “Florence” (today in the Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow), some “Synthetic Urban View” and “Parisian Boulevard in the Evening” (also at the Tretyakov Gallery). The later Futurist work was the closest to the Orphic trend being elaborated in Paris by Picabia and Kupka, among others (Apollinaire coined the term Orphism to describe their work). Like in Giacomo Balla’s work, the energy released by the centrifugal motion in Exter’s painting brings the pictorial planes to a kinetic state of such extreme incandescence that all illustrative reference to forms is superseded.

In the wake of this exhibition, Exter developed a privileged relationship with Malewicz. He let her into his Moscow studio during the summer of 1915 when he was working in utmost secrecy on his first Suprematist paintings. In all likelihood, their discussions about Cubism stimulated Malewicz to conceptualise his definitive view on the new non-objective art: Suprematism. This is how Exter became the first to present two abstract paintings by Malewicz to the public, several weeks before the first show of Suprematist painting at the revolutionary 0,10 exhibition in December 1915 in Petrograd.

The preview organised by Exter opened in Moscow on 6 November 1915. The Exhibition of Contemporary Decorative Art was its title and it was held at the Lemercié Gallery. It benefitted from Exter’s vitality and her modernist connections as much as from the financial support of Nathalie Davydov, herself a painter and a close friend of Exter’s from Kiev, who was a long-time patron and promoter of folkloric decorative art and later became a close follower of Malewicz. The roots of this exhibition in Moscow can be traced back to Paris, where in the spring of 1914 a similar event was planned with a view to grounding the new Cubo-Futurist art “in life”. Sonia Delaunay, Balla and the English Vorticists had already taken decisive steps in this direction. Because of the war, France would have to wait ten years for the Modern Decorative Arts (Exposition des Arts décoratifs modernes), an exhibition to open its doors in 1925. Exter, who was back in Paris at the time, participated in this event as a member of the sizeable Russian section.

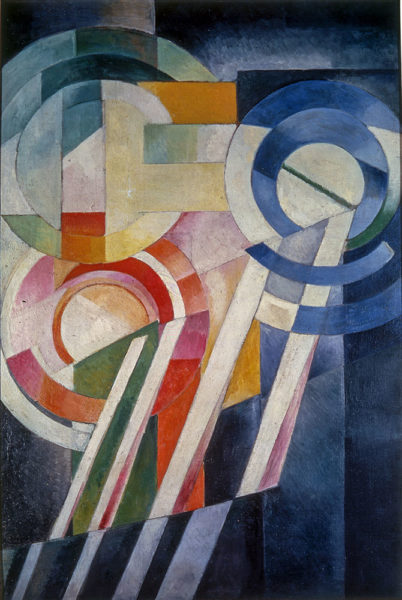

Working at first in Paris and later in Kiev, the artist pursued her very own pictorial avenue. Her interest in Italian Futurism (Balla, Boccioni, Severini) and her personal practice of Cubism in its most abstract form – which Apollinaire termed Orphism – ineluctably led her painting toward greater abstraction, as evidenced in Urban Landscape (Slobodskoy Museum, Russia). The transition took place in the winter of 1915-1916. In this work, the figurative reminiscences are absorbed by the mutation of colours to autonomous, purely non-objective planes. Significantly, when a few years later the work was sent by the Moscow Museum Office to Slobodskoy it was designated under the title “Non-Objective Composition”, since that is how it was perceived at the time.

In Kiev, away from the competitive atmosphere of Moscow and especially from the stylistic interferences that resulted from the fierce avant-garde competition, Exter escaped the hold of Suprematism. Given the Western foundations of her artistic conceptions, this enabled her to chart her own autonomous course, to develop a personal vocabulary and an original constructive logic. As a result her painting differed from anything being done in Moscow.

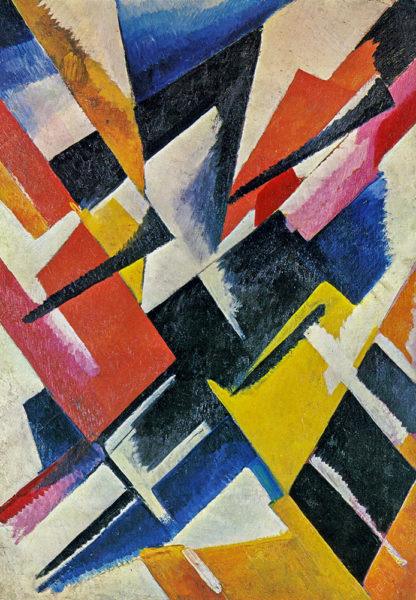

In 1917 and 1918, her concentration on the energy of colour and the constructive force it generated led Exter to compositional schemes that did not owe much to the existential dialectics of Suprematist forms. Unlike the principle of absolute autonomy of non-objective planes, which was the maximalist aesthetics forcefully asserted by Malewicz’s Suprematism, Exter’s planes of colour maintain productive relationships with one another. Derived from the logic of Cubism, this “constructive inter-reaction” yields new formal relationships and new compositional schemes. Out of this dialogue of energy, a construction is born in which each component is woven into a fabric of creative interdependence.

Exter’s abstract work from this period displays a great many compositional constellations. Rare are the painters of her generation to have produced such a variety of compositional types (on could mention Kupka, Franz Marc, Otto Freundich). The energetic logic that defines this autonomy of “liberated colour” is projected into a “meta-stylistic” state, because energy is an extra-formal concept by definition. This energy circulates wildly in a new freedom that spans utmost rigorous geometry and the nebulous lyricism of an expressionist-type abstraction – situation where colour is manifested in a state of gestation (see the abstract painting at the Wilhelm Hack Museum in Ludwigshafen).

The freedom that resulted from this purely energetic conception of colour reached a new level at the “constructivist” 5×5+25 exhibition held in Moscow in September 1921. The brief statement by the artist in the catalogue clearly expressed her colourist approach: “the works attest to solutions of colour relationships, the reciprocal tension that results, the rhythms and the passage to a construction of colour alone, construction founded on laws of autonomous colour.” The results of this maturity of colour energy are to be found in a series of abstract works that were exhibited in the fall of 1922 in Berlin (Van Diemen Gallery) and in 1924 at the Venice Biennale. The paintings shown in Venice contributed to establishing the artist’s European reputation, which continued to grow in the following decade.

Exter’s output for the stage during the same period was impressive: she made costumes and sets for Romeo and Juliet (1921), The Comrade Hlestiakov, The Death of Tarelkin. She worked in Kiev for Bronislava Nijinskaya and in Moscow for Goleizovsky, dancer and acrobatic gymnast for whose shows she created in 1922 and 1923linear constructions of unprecedented audacity. The oblique spacing of platforms and ladders soaring in Goleizovsky’s purely rhythmic (abstract) shows impressed her contemporaries as much as the virtuosity of vertical platforms in the earlier staging of Romeo and Juliet. Ten years later, Tairoff recalled this innovation and asserted that “inspired by her cubist experience” Exter had “invented the vertical stage” as early as 1921.

Exter’s revolutionary theatre work based on her novel method of dematerialising the decor was described by Simon Lissum in 1931 in the following terms: “It is light that forms everything at once: the volumes, the costumes, and so on are all light values”. Just as abstract art had eliminated the reference to the extra-pictorial object, Alexandra Exter, the Columbus of modern decor, eliminated sets painted on canvas and replaced them with pure light to create so very powerful immaterial decor.

Shown in 1924 in Vienna at the New Theatrical Techniques exhibition, her sets and costumes established her international reputation from one day to the next. The European tour of Tairoff’s Chamber Theatre (Berlin and Paris in 1923) had already prepared the ground. When she arrived in Paris at the beginning of 1925, she was immediately invited by Fernand Léger to join his Modern Academy where she taught stage design (abstract painting aroused less interest at the time). From then on Exter worked mainly in the field of the performing arts, in France, Italy and England where she designed the costumes and some ballet decors, including Nijinskaja’s.

Exter’s theatre work culminated in 1930 in the publication by the Galerie des 4 Chemins in Paris of an album of fifteen stencils, with a preface by Alexandre Tairoff. It was the occasion of her first one-woman show in Paris of stage sets and costumes at the gallery. At the same time, she took part in the abstract Cercle and Carré exhibition and journal that established abstraction once and for all as a respectable art form in Europe. Exter’s theatre work also crossed the Atlantic and was featured at the International Theatre exhibition in New York and the following year in the famous Machine Age Exhibition mounted by Alfred Barr at the new Museum of Modern Art in New York. The same year, Exter had an exhibition at Herwarth Walden’s Der Sturm gallery in Berlin, a show entirely devoted to her theatre work. It seemed as if her painting was already irremediably relegated to oblivion.

A year later, her Slovakian student Ester Šimerova successfully put together a big solo exhibition of Exter’s work, subtitled Divadlo (theatre). With 116 entries in the catalogue, this show at the Museum of Decorative Arts in Prague (Uměleckoprůmyslové museum) was the most extensive exhibition of the artist’s theatre work ever organised. The costumes Exter designed for Aelita could hardly have been appreciated as much as in Prague, in the country where Karel Capek had coined in 1920 the productivist neologism “robot” destined to figure a new category in the repertoire of European culture. This exhibition, however, turned out to be the swansong of Czech modernity and of Exter’s career. The invasion of Sudentenland by the Wehrmacht set in motion the sinister hecatomb of the Second World War, which began a few months later in early 1939.

For Exter was in fact one of the first in a modernist movement marked by the emergence of abstract painting to benefit from quite a bit of attention. Witness the many Russian articles on her work published in the 1910s. The renowned art critic Jakob Tugendhold, an expert on modern French art, was the author of an illustrated monograph on Exter, published in 1922 in Berlin in four versions – Russian, German, English, and French – proof that the publisher saw the European, and even international, prospects of the artist. Fifty years went by before another monograph on Exter was published, fifty years that corresponded to the totalitarian interruption in a century that proved to be merciless with the Prometheuses of art.

The first posthumous exhibition of the artist was held in Paris in 1972 and a second organised in Moscow in 1987, half a century after the last exhibition in her lifetime. The place that she deserves in the history of abstract painting remains to be asserted.

Ce texte fait partie d’une notice, rédigée par Andréi Nakov pour l‘Encyclopédie de l’art moderne, ouvrage collectif en plusieurs volumes, à paraitre en langue russe à Moscou en 2013.