The collapse of the Soviet Union flooded the art market with works of often uncertain provenance. German and Israeli police now believe they have broken up a ‘cartel’ suspected of selling hundreds of Russian avant-garde forgeries worth tens of millions.

Dusk was falling over the foothills of the Ural Mountains as art lovers from Perm, 1,150 kilometers (700 miles) east of Moscow, witnessed a minor sensation. On this evening in May 2005, the state-run art gallery on Komsomolskiy Prospekt presented a series of spectacular Russian avant-garde masterpieces that had unexpectedly re-emerged from the dim recesses of history. Among these works were a composition by El Lissitzky, a ‘Portrait of a Woman in Blue’ by Aristarkh Lentulov and a painting by Kazimir Malevich that had been unknown until then even within the art world.

This extravagant exhibition came from the private collection of a mysterious businessman named Edik Natanov, an art lover who attended the show’s opening in a dark suit and black T-shirt, presenting his motivations as altruistic. ‘I wanted to show people something they had never seen before’, Natanov told a television crew, smiling modestly.

Perm’s art enthusiasts didn’t get to see the jewel of Natanov’s collection, though. ‘K19’, an avant-garde effusion of color bearing Wassily Kandinsky’s well-preserved signature, was at an auction house in Milan at that moment, where it was up for sale for several million euros.

In this oil painting, dated 1919, respected Moscow art professor Valery Turchin believed he recognized not only Kandinsky’s complex visual language, but also the ‘erratic glow of spiritualized matter’. Additionally, Turchin wrote in an exhibition catalogue, the work contained unmistakable religious references to the apocalypse and the Last Judgment.

The secular justice system, however, was not quite so effusive in its praise of the supposed masterpiece. In fact, a Milan criminal court ruled earlier this year that ‘K19’ was nothing but a forgery. Working on behalf of the Italian court, appraisers had determined that the purported Kandinsky could ‘hardly’ have been painted in 1919 and must have originated decades after the artist’s death, in 1944. In fact, they found that some of the paint on the canvas was ‘not even completely dry’.

Rediscovered

Germany’s Federal Criminal Police Office (BKA), headquartered in Wiesbaden, has taken an interest in the case as well. BKA investigators believe that two of Natanov’s long-standing business partners, who sough to sell the purported Kandinsky painting in Italy, are the ‘marketing directors’ of a cartel that, in their view, has flooded the art market with forged works of Russian avant-garde artists. According to the BKA, this group ‘operates internationally’ and has sold at least 400 paintings, each for ‘four-to seven-figure euro sums’ and generally to private collectors. The total profits from such activities – if the BKA’s suspicions prove true – reach at least into the double-digit millions.

This places the art world at the cusp of a new forgery scandal sure to overshadow all previous ones. In the past, forgers tended to focus primarily on the œuvre of individual artists. Wolfgang Beltracchi, for example, hoodwinked the art world with works in the style of Max Ernst and Heinrich Campendonk, while a would-be German ‘count’ put several hundred Giacometti forgeries into circulation.

But now an entire epoch – the Russian avant-garde – has become suspect. The market is flooded with works from the first decades of the 20th century that are said to have been newly discovered. But few can prove their provenance beyond a doubt.

There are historical reasons for this chaos. After the 1917 October Revolution, Soviet museums acquired avant-garde works en masse. Some painters, including Malevich, even made copies of their own works to meet the production goals of Lenin’s massive state. Then, under Joseph Stalin, the only works of art that counted were eye-catching, monumental pieces in the Socialist realist style, while the abstract work of avant-garde artists was denounced as ‘decadent and bourgeois’.

The flourishing trade in Russian avant-garde art didn’t take off in a big way until the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the ‘rediscovered’ paintings often had thrilling stories to back them up. Some came from secret government warehouses, one hears, while others were carefully hidden family possessions.

Operation Malefiz

While investigating suspected money laundering, agents of Lahav 433, a new law-enforcement organization known as the ‘Israeli FBI’, stumbled upon this scene more or less by chance. They discovered that some of their suspects were apparently also dealing in art forgeries. When they discovered a gallery in the western German city of Wiesbaden that they suspected of crooked dealings, they brought their counterparts at Germany’s BKA into the investigation.

In a covert operation, German and Israeli police monitored telephone conversations and email correspondence while tracing shady cash flows around the globe. In June, the investigators finally struck in a concerted action under the code name ‘Malefiz’ (the name of a German board game, but also an obsolete word for a crime or misdeed). They searched apartments, galleries and offices in both Israel and Germany, froze Swiss bank accounts and confiscated hundreds of works of art.

In a single furniture store in Wiesbaden, BKA agents discovered nearly 1,000 suspicious paintings, drawings and watercolours that were apparently being stored for future sale. The storeroom was not climate controlled and lacked any special security system – hardly a way to store goods worth millions.

The raid led to the arrest of two art dealers, Itzhak Z., 67, and Moez Ben H., 41, identified in this way due to German privacy laws. According to the files on their case, the two are strongly suspected of ‘fraudulently selling for profit forged Russian avant-garde works of art presumably produced in Israel and Russia’. Among the two suspects’ offerings were works from the same ‘Natanov Collection’ that had caused such a stir at the 2005 exhibition in Perm.

A ‘Family Inheritance’

That collection, also the source of the supposed Kandinsky painting ‘K19’, was largely unknown to German art experts. Only the small art magazine Artprofil devoted a lengthy article to this ‘private, museum-quality art collection’. According to the article, Edik Natanov hails from a distinguished family from Samarkand, Uzbekistan, that has collected art ‘for generations’.

The grandfather, Mikhail, was supposedly a ‘well-traveled scholar’ who headed a collective farm during the Soviet era, acquiring most of the works in the current art collection in the 1950s. After his death, according to Artprofil, these paintings passed into the hands of his son and then, in 1995, to his grandson Edik.

Whether that story is truth or fiction, the fact remains that, in early July 2002, five items from the collection, including the dubious Kandinsky, turned up on loan to an art museum in Pereslavl-Zalessky, a town 140 kilometers (87 miles) northeast of Moscow. The delivery receipt was signed by Edik Natanov.

At the time, the heir of this putative art fortune was president of a diamond trading company based in Israel while also getting involved in the gallery business in Wiesbaden. In August 2002, he founded his own art dealership together with Itzhak Z., who is now in prison, and another partner, Daniel S.

The three business partners rented upscale commercial space in a historic building on Wiesbaden’s Taunusstrasse and invested several hundred thousand euros in renovations, with the plan of creating an exclusive exhibition space. They also installed a walk-in safe for the paintings in the building’s cellar. And they were quick to give their company an international-sounding name, combining the first letters of each of their last names to call themselves ‘SNZ Galeries’, although they evidently failed to note that in English the word ‘galleries’ is spelled with two l’s.

Fake It Till You Make It

By this point, the trade in Russian avant-garde art was in full swing. By March 2002, a piece from the ‘Natanov Collection’ found its way to an auction house in Frankfurt. This constructivist portrait, titled ‘The Writer’ and supposedly painted by Nadezhda Udaltsova between 1915 and 1920, was valued at €100,000 ($130,000). But then, the auctioneer recalls, he received a call telling him the painting was a fake. To be on the safe side, he pulled it from the auction.

Business got better as time went on. In 2004, the Triton Foundation, an art foundation established by a wealthy Dutch couple that had made its fortune in shipping, purchased a ‘Natanov’ piece, ‘Dynamic Composition’ by Alexandra Exter. Several hundred thousand euros are believed to have changed hands.

According to a Russian exhibition catalogue published in 2003, at that time, Natanov’s collection included at least 18 Russian avant-garde pieces, including two Malevich works, two Jawlenskys and the supposed Kandinsky composition ‘K19’.

It was with this last painting that Itzhak Z., Natanov’s fellow gallery owner, evidently hoped to make millions. Original Kandinskys come onto the market only rarely – and they fetch top prices.

The hurdles that must be cleared to make such a sale, however, are high. Any piece that hasn’t received approval from the Paris-based Société Kandinsky is more or less impossible to sell on the established art market. The society, founded by Kandinsky’s widow, Nina, keeps close watch over the artist’s body of work, and auction houses only accept pieces listed in the society’s catalogue.

‘K19’ didn’t have that stamp of approval. So, to sell the painting, Natanov’s business partners needed a broker who could connect them with the gray market.

Business Ups and Downs

One such man was an Italian named Andrea N. At the time, N. was working for a gallery in Paris that bought and sold works by Modigliani and Picasso, but he was not averse to doing a little business on the side. In exchange for a hefty commission, N. agreed to look for a buyer for ‘K19’.

In February 2005, Moez Ben H. traveled to Paris. He was executive director of SNZ Galeries at the time and had talked up the fabled Kandinsky work to Andrea N. on an earlier visit. This time, he brought the masterpiece with him, handing it over to the Italian middleman at his apartment on Avenue Émile Zola, on the Left Bank of the Seine.

Andrea N. stored the painting in his wardrobe. His housemate kept an eye on the valuable artwork whenever he was out, N. later told the court, since he was a writer and ‘only left the apartment to run errands’.

Soon it seemed N. had found a way to market the painting. He took ‘K19’ out of the wardrobe, packed it and flew with it to Italy. The supposedly valuable Kandinsky work made the journey in the cargo hold, packed in among the other passengers’ suitcases. In Milan, N. met up with a former antiques dealer who ran a small auction house on Corso Garibaldi. The dealer showed ‘K19’ to several prospective buyers over the course of the following months, but no one wanted to buy it.

The gallery owners back in Wiesbaden didn’t let that stop them. Having finally finished renovations on their exhibition space on Taunusstrasse, they threw a grand opening party attended by the local smart set on November 7, 2006. Meanwhile, the demand for unknown Russian avant-garde works seemed to be increasingly, and this included paintings from the ‘Natanov Collection”. In April 2007, for example, the ‘Composition’ supposedly painted by Alexandra Exter around 1913 sold at auction in Berlin for a possibly record-breaking €310,000.

Then SNZ Galeries received good news from Milan : A wealthy businessman was willing to pay €3 million for ‘K19’. The painting was delivered to the businessman’s office in late 2007 in exchange for collateral in the form of securities ostensibly worth millions of euros.

But disagreements arose over the payment, as it seems both sides of the deal were not above using tricks. While the businessman wanted to pay for the alleged Kandinsky with shares in an American real estate fund, Natanov’s business associate Z. wanted to see cash. An intermediary, apparently worried about his commission, filed charges against the buyer, claiming his securities turned out to be useless junk.

In July 2008, when Italian police arrived at the businessman’s office to retrieve the painting for the seller, the erstwhile buyer retorted that it was a forgery anyway. In the end, police confiscated the painting – and launched a criminal investigation of everyone involved.

Things went downhill from there for the Wiesbaden gallery. Former employees say Z. began visiting the local gambling hall more frequently and that Natanov was nowhere to be found. Moez Ben H. resigned as executive director in late 2009 and, a year later, the leaderless company was forced to abandon its premises. H. went on to become a seller of secondhand goods in Wiesbaden.

Unanswered Questions

But the BKA uncovered further shady business dealings. H. and Z. are suspected of having sold at least seven more forgeries of Russian avant-garde art since 2011, for a total of over €2.53 million. Six of these supposed masterpieces – including three by Natalia Goncharova, one by Malevich and another by Lissitzky – ended up in Spain. A collector in Germany’s Rhineland region paid €450,000 for another painting, this one in the style of Lyubov Popova.

Proving whether these and other recovered paintings are indeed forgeries will require the BKA to conduct extensive investigations – and a separate one for each individual work. The only piece so far proven to be a fake is the purported Kandinsky.

Investigators still need to determine where the fakes were made and how many people painted them. At least some of the paintings, investigators believe, may have been produced by a 53-year-old painter in St. Petersburg, who was caught in the act of forging three paintings simultaneously in Tel Aviv on January 2013.

Natanov, meanwhile, has publicly and repeatedly stressed that he had his artworks extensively appraised for authenticity, although he claimed to trust ‘only experts from Russia’.

Was the collector deceived by his business associates ? Or did he know about their activities and decide to offer up his family history to lend a credible legend to their forgeries ? German investigators have not charged Natanov with any crime. He claims he no longer has anything to do with this business and that he parted ways with business partner Z. years ago because they supposedly ‘didn’t get along’.

Natanov says he ‘simply left’ the supposed Kandinsky, which had ‘been in the family for years’, with Z., and that he ‘didn’t received any money for it, nor did I ask for any’. He also says that’s just the kind of person he is. He still has his art collection, but he declines to reveal how many pieces are in it.

Defense lawyers for Itzhak Z. and Moez Ben H. likewise declined to comment on the accusations. Both men were tried in Italy, where on February 19, 2013, the third chamber of Milan’s criminal court sentenced them to suspended sentences of one year each for their involvement in the sale of the forged Kandinsky. The verdicts, however, are not yet legally binding.

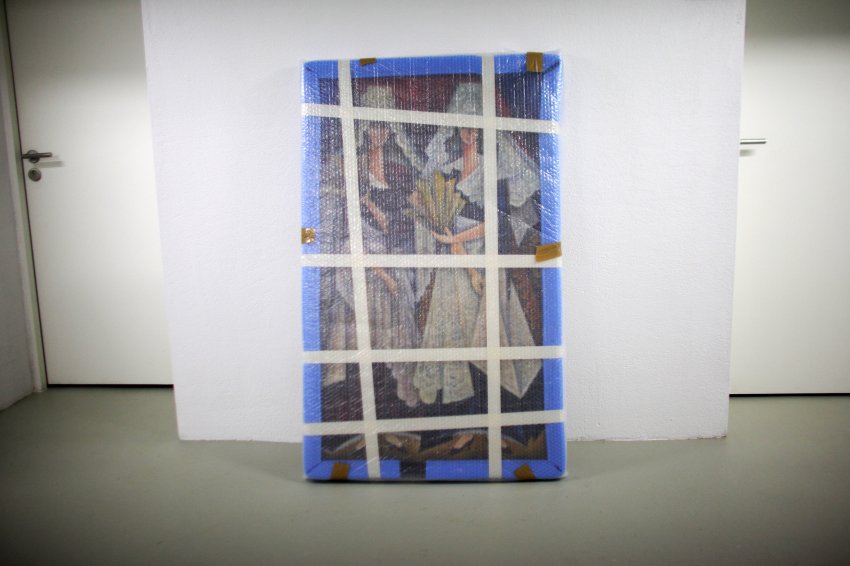

As for ‘K19’, the painting is now stored alongside confiscated antiques in a slightly dilapidated side room of a former imperial residence in Monza, a city just north of Milan. The residence serves as an evidence storage facility for the Carabinieri, Italy’s paramilitary police force.

By Sven Röbel and Andreas Wassermann, DER SPIEGEL n° 31, dated 29th july 2013. Translated from the German by Ella Ornstein.

Leave a Reply